William E. Parker

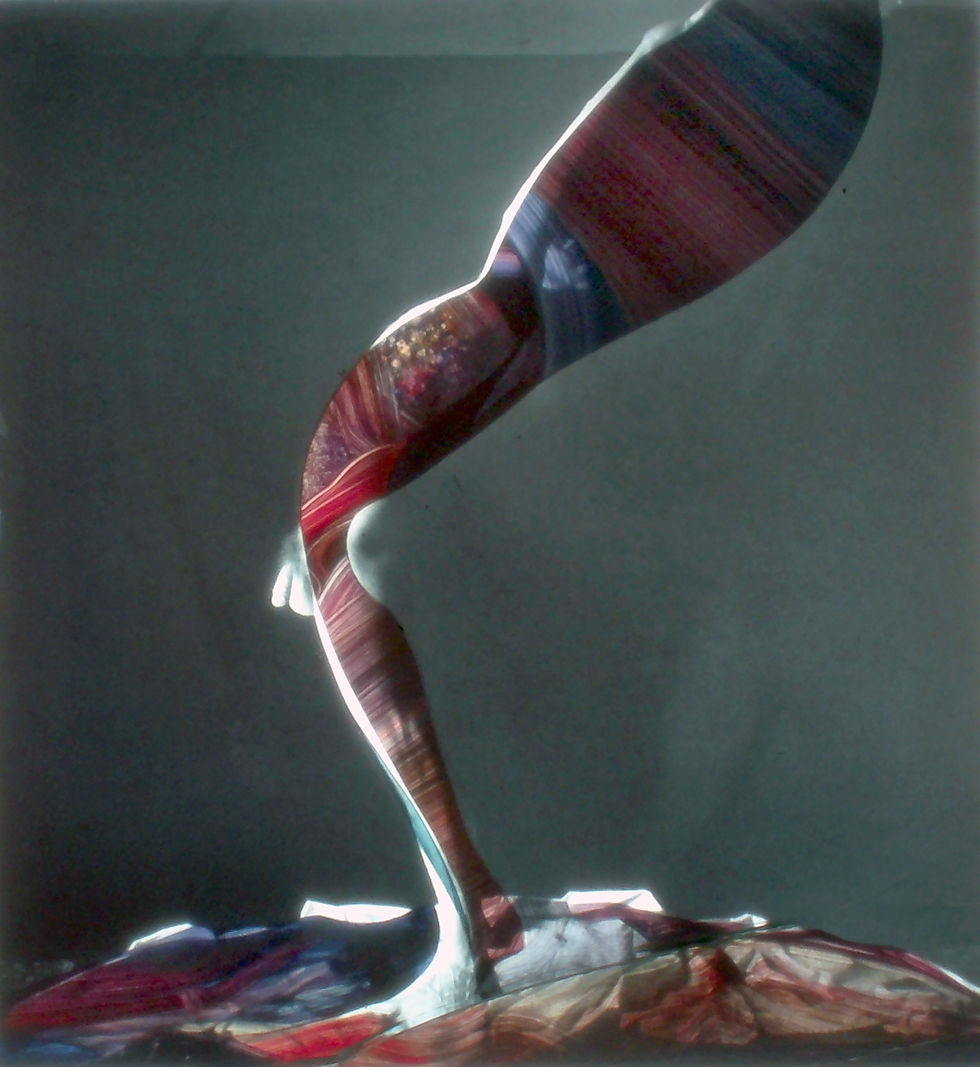

Tattoo/Stigmata Series: 1978-1981

Oil emulsion on black and white silver print, 16" x 16"

Oil emulsion on black and white silver print, 15" x 15"

Oil emulsion on black and white silver print, 16" x 16"

Oil emulsion on black and white silver print, 16" x 16"

(Double click on the image to view the gallery without interference of arrows and captions)

Keeping in mind that all of the images in Parker’s four photographic series strive to recuperate the eros identity of the male figure, the Tattoo/Stigmata images do so most overtly with color. The imprinting, or tattooing, of the male body with rich multicolored striations or bold blocks and bands of highly saturated pigment reassert the male figure’s sensuality. At the same time, Parker reverses the centuries-long practice of concealing or minimizing genitalia in artistic representations of the male body. The nudity in these images is unashamed and frank. Among the many analogs in the mimetic tradition informing this work, I recall my father’s specifically identifying the ithyphallic bird-headed shaman figure from the Hall of the Bulls in the prehistoric cave at Lascaux, with its astonishing polychromed paintings of bounding bison and horses. As theorized by Sigfried Giedion in The Eternal Present: The Beginnings of Art (New York: Pantheon, 1962)—one of my father’s most beloved books—the shaman figure stands in excited trance, vulnerable within the awesome presence of wild beasts. In short, whether one buys Giedion’s interpretation or not, Parker, as an image-maker, had this figure and its vulnerability in mind while working on male nudes in ithyphallic profile posture in the Tattoo/Stigmata group. Some of the figures in this series are wrapped in gauze, as if cocooned and straining to move. The cocooning motif, related to stigmata as a site of wounding and pain, is similarly linked to Parker’s project to draw attention to the vulnerability of the male body. During a court hearing, where he had to defend his use of nudity in these images, Parker identified as analog to the wrapped figures, Michelangelo’s prisoner-slave sculptures, where male figures struggle to wrench themselves free of the stone matrix imprisoning them.

Parker’s project in Tattoo/Stigmata, particularly its candid male nudity, had its cost. These photographs were exhibited during a period of contention surrounding the arts. Citizens began to complain about their tax dollars going to support artworks they deemed obscene or offensive, and throughout the 1980s, demands for the government to defund the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grew ever louder. Parker was among a group of artists whose works were seized and damaged by police during their raid of an art exhibit at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence. Under threat of arrest if they entered the state, the artists formed a collective and sued the Providence Police Department (see RISD Exhibition Busted; Artists Sue Police). At length, the artists won their constitutional case and created a legal defense fund for artists whose First Amendment protections are under assault. Nonetheless, these works are still occasionally shadowed by accusations of impropriety.

Let’s close on Bill Parker’s own words about this series, which more fully announce his techniques and aims.

The figures in the Tattoo/Stigmata series reflect gestures, postures, and iconography apparent in the history of painting and sculpture, such as ithy-phallic representations of the male body evident in Pompeian, Graeco-Roman, and Egypto-Roman art; Medieval and Renaissance statuary; early paintings and drawings defining shrouded figures such as Lazarus or Christ; stigmata themes and classicizing representations of the male form. Each work in the series is a black and white silver print, overpainted by hand with oil-emulsion; thus, each work is unique and non-repeatable. Stemming from my reaction to issues announced by John Berger, [Marxist] British writer and critic, particularly . . . his The Moment of Cubism (1969), The Look of Things (1971), Ways of Seeing (1972), and About Looking (1980), wherein he suggests that, throughout the history of post-Medieval Western art, the female nude is typically defined as “object, property, and surveyed presence,” as a subject representing primary exploitation by a masculine sighting [or siting] consciousness, the Tattoo/Stigmata series represents the male figure in visual circumstances no less candid or vulnerable. The figures are iconically represented, gesturally posed, and amplified by hand-applied oil color to connote the renascence of an eros, an emphatic corporeality and sensuality the male body once shared with that of the female, an eros that in recent centuries, despite covert or academic evidences, has been denied or assiduously avoided in images of the male nude.

—Catherine Nevil Parker